Books as ambitious, layered, and soul-deep as the ones we already call great.

There are books so emotionally complete, so structurally vast, they leave you wondering what could possibly come next. You finish Anna Karenina, Sentimental Education, or Père Goriot and feel a kind of silence — not just at the end of a story, but at the edge of a literary category. As if you’ve touched something definitive. Irreplaceable.

But it isn’t. And the truth is, the canon — as we’ve inherited it — is not the whole conversation. There are novels of equal scale and complexity that live just outside its borders: untranslated, unassigned, unnamed in the usual lists of “the greats”.

What follows isn’t a supplement or a themed list. Some of these books echo familiar structures; others break from them entirely. What unites them isn’t subject, style, or geography — it’s ambition. These novels don’t follow the canon. They belong on the same shelf.

If you loved Anna Karenina, read La Regenta

Leopoldo Alas “Clarín,” 1884–85

Ana Ozores, a judge’s young wife in a provincial Spanish city, finds herself caught between religious fervour, romantic temptation, and a kind of moral limbo. But La Regenta doesn’t tell this story in crescendos — it unfolds in slow psychological weather. Emotional turning points are often internal: a lingering thought, a moment of prayer, or a glance that goes unanswered.

Clarín maps out the inner terrain with rare clarity. We follow Ana’s struggles not just through dialogue or action, but through long interior monologues that trace every shift in her reasoning, repression, and doubt. The novel’s force comes from how thoroughly it captures emotional suffocation — not with melodrama, but with accumulation.

It’s not an echo of Anna Karenina. It’s her peer — a parallel story of desire and duty, written with colder light and deeper restraint.

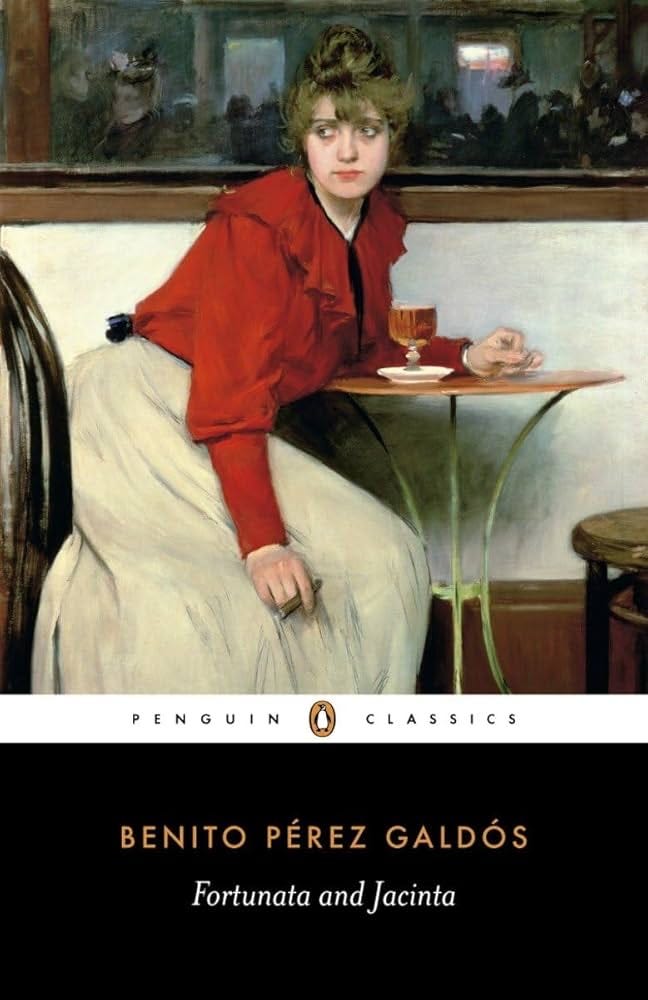

If you love Balzac, read Fortunata and Jacinta

Benito Pérez Galdós, 1887

At nearly a thousand pages, Fortunata and Jacinta builds a world as intricately constructed as anything in Balzac’s Comédie Humaine. Galdós gives us a cross-section of Madrid society — bourgeois families, religious radicals, corrupt doctors, desperate lovers — and sets them spinning in a web of inheritance, scandal, and social pressure.

The novel follows two women tethered to the same man: Jacinta, the refined wife who cannot bear children, and Fortunata, the working-class mistress whose presence refuses to be erased. Their lives collide through schemes, breakdowns, and reversals — but always with a realism that resists simplicity.

Galdós moves with Balzacian breadth — the city as organism, characters as functions of their class and time. But he also zooms inward. His moral vision is more personal: less about satire, more about consequence. Fortunata herself is among literature’s most vivid tragic women — erratic, sensual, at times volatile, but always painfully real.

Fortunata belongs with literature’s most complex women — a cousin to Zola’s Nana, Eliot’s Dorothea, and Tolstoy’s Anna. But she isn’t tragic in the refined, classical sense. She’s volatile, raw, vividly alive — written from the nerves, not the blueprint.

She isn’t punished. She isn’t saved. Galdós gives her dignity, not resolution. The novel’s greatness lies in its refusal to flatten her — or anyone else.

If you love Père Goriot, read The Poor Gentry

Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, 1859

Saltykov-Shchedrin is rarely read in English, but The Poor Gentry (also translated as The Golovlyov Family) is one of the darkest, sharpest dissections of aristocratic rot in all of 19th-century literature.

Like Balzac, he writes about decline and delusion. But where Balzac gives us ambition corrupted, Saltykov gives us lethargy weaponised — a family eaten alive from the inside by spiritual stagnation, greed, and emotional cruelty. There’s no rise or fall — just slow decay.

The prose is direct, the satire more moral than comic — cold, relentless, and steeped in contempt — and the emotional atmosphere sits somewhere between Bleak House and The Brothers Karamazov, but without warmth or redemption. It’s as structurally sound and morally confrontational as anything in the canon — just ignored because it’s so brutally unsentimental.

If Sentimental Education left you hollow, read The Maias

José Maria de Eça de Queirós, 1888

This is a novel about ideals collapsing quietly over time. Carlos da Maia is born into wealth, education, and taste — but instead of acting, he drifts. He writes a book he never finishes. He pursues a woman he cannot keep. He believes in reform, but does nothing to change the country or himself.

Set in a decaying Lisbon filled with failed writers, idle politicians, and melancholy beauty, The Maias captures what it means to waste not just an opportunity, but a life. Like Flaubert, Eça builds scenes with irony and elegance — a conversation over tea, a letter that never gets sent — and lets their weight accumulate.

Eça’s restraint isn’t absence — it’s precision. And what’s left behind is just as haunting. His tone is pure Flaubert, but the emotional residue feels closer to early Henry James or even Proust, where time and taste slowly eclipse action.

Its brilliance is in the precision. Every missed step is subtle, every disappointment delayed. When ruin comes, it feels inevitable not because of fate, but because of inertia. It’s a novel that sinks rather than strikes — and leaves behind a quiet devastation.

Widening the Shelf

Once you start reading outside the usual canon, you see how much of it is simply what got translated, taught, or repeated. These novels aren’t hidden because they’re lesser. They’re hidden because they weren’t inherited. The difference is structural, not artistic.

What unites these books isn’t that they mirror familiar stories. It’s that they answer them — not with imitation, but with equal force. They don’t chase the canon. They expand it.

Everyone’s read Tolstoy and Flaubert. But what if the clearest vision of decline wasn’t written in Moscow or Paris — but in Lisbon, or Oviedo? These aren’t reflections or footnotes. They’re part of the literary conversation we’ve yet to fully acknowledge.